70 years later, a World War II airman returns homeDiane Moore/Special to the Sun

An honor guard carries the casket of Tech Sgt. Hugh Francis Moore at Philadelphia Intl. Airport. His remains, discovered in New Guinea in 2001, were identified by DNA testing. He had been MIA for over 70 years after his plane was shot down in WWII.

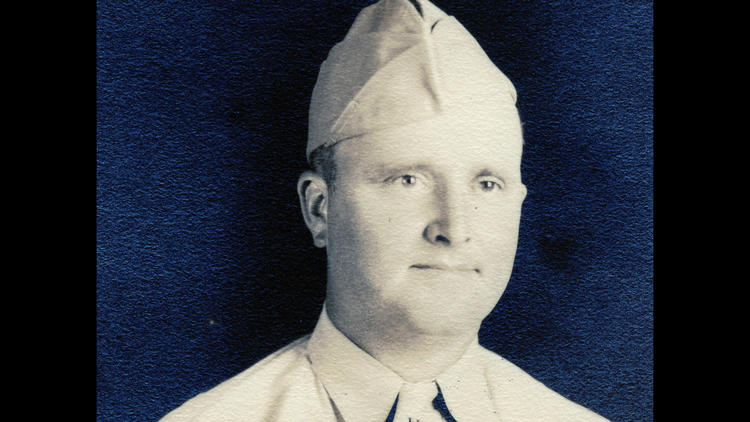

Technical Sergeant Hugh Francis Moore

Technical Sergeant Hugh Francis Moore, far right, with some of his military buddies.

Charles Moore is the nephew of Technical Sergeant Hugh Francis Moore.

By Jean Marbella,

The Baltimore Sun

After 70 years, Sgt. Hugh F. Moore coming home to be buried in Maryland.

Charles Moore was about 7 years old at the time, in bed and asleep, when his father and his Uncle Hugh woke him up.

Hugh F. Moore was in the Army Air Forces and had just received orders that would ultimately take him to Papua New Guinea and into a massive bombing campaign against the Japanese in World War II.

"He had this cloth badge, something you'd sew on a shirt, and he wanted me to have it," Charles Moore, 79, recalled Monday. "That's the last time I saw him."

On April 10, 1944, Technical Sgt. Hugh F. Moore and 11 fellow crewmen were shot down in their B-24D Liberator bomber. On Veterans Day on Tuesday, more than 70 years later, the remains of the 36-year-old airman will be buried in his native Elkton, where his survivors will mark a long-delayed homecoming.

While the remains of three of the crewmen were found after the war, the other nine were deemed unrecoverable in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. But in 2001, the wreckage of Moore's aircraft was located, leading to an excavation and recovery of remains and other material.

Using family members' DNA, Moore was identified Sept. 5.

"It's almost like the marrying of 'Cold Case' and 'CSI,' " said Lt. Col. Melinda F. Morgan, a spokeswoman for the Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office. "You have to do a lot of historical research, as well as genealogical research to do the DNA testing."

Morgan said the process of retrieving the remains and other material from the aircraft, and then identifying the airmen, took a long time because of the number of crew members. They were identified by the Defense Department's Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command, or JPAC, which is dedicated to identifying the approximately 83,000 Americans unaccounted for from past conflicts. The unit has even been able to put names to the remains of recovered Civil War sailors.

More than 70 of Moore's surviving relatives will gather at Cherry Hill United Methodist Cemetery in Elkton, where he will be buried with full military honors. He was one of nine children born to Edward and Emma Louise Scarborough Moore, and he joined the Army in July 1942, according to an obituary posted by Hicks Home for Funerals in Elkton.

Some of his relatives, including Charles Moore, a resident of North East, met the flag-draped casket at Philadelphia International Airport on Sunday. Traveling from Honolulu's Pearl Harbor, where JPAC is based, Sgt. Moore's casket was escorted by Army officials to Elkton.

On Tuesday, there will be a memorial service at Hicks Home for Funerals in Elkton, followed by the burial.

"It's an opportunity to know the homecoming has finally come to an end," said Diane Moore, Charles Moore's daughter. "It was a long time coming."

Ed Warrington, 75, a nephew who lives in Townsend, Del., just north of Dover, said his sister and her daughter, both of whom have since died, provided DNA samples to the Army that led to the identification of Sgt. Moore's remains. One way JPAC identifies remains is through mitochondrial DNA, which passes through maternal family lines.

For Warrington, a semiretired farrier, the return of the remains brings back memories of the letters his uncle used to write him and the toy airplanes he would receive as gifts.

"He told me he was an engineer" on the crew," Warrington said, recalling that his uncle told him, " 'That means I know everything about the B-24 and how to fix it.' "

Warrington said his mother Wilamina was close to her brother, and the family never gave up hope he would be found.

"She would never let anyone forget him," Warrington said. "A couple of months ago, I found a little pocket diary of hers. She only had a couple of entries, and on the date Uncle Hugh went down, she had written, 'Hugh declared missing' on that day."

The family remains in awe that the military continued to search and try to identify such long-ago casualties of war.

"It's pretty amazing," said Diane Moore, a communications supervisor for the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, who lives in Lancaster, Pa. "It shows the value they place in the soldier."

Moore's parents had bought a plot for him in the Cherry Hill cemetery in the 1940s in case the airman was found, according to the funeral home, and they also placed a memorial marker there. He had grown up on the family's farm, and worked at a paper mill and a supply company before joining the Army in July 1942, according to his obituary.

According to the Defense Department, Moore's plane was one of as many as 60 B-24 Liberators from the 5th Air Force that attacked enemy anti-aircraft targets and airfields near Hansa Bay on Papua New Guinea's northern coast. His aircraft, a heavy bomber, was nicknamed "Hot Garters" for reasons that are unknown today, according to the Defense Department's Morgan.

The department says witnesses reported that as "Hot Garters" broke off to begin its bombing run, it was hit by flak from Japanese anti-aircraft guns and its No. 2 engine caught fire. A second fusillade provided the fatal blow, and the aircraft was consumed in flames, coming apart in midair and crashing into the jungle.

Four of the crewmen were able to parachute from the aircraft, according to the Defense Department, but they were taken prisoner and died in captivity. Moore died in the crash itself, Morgan said.

News accounts at the time describe a massive attack on Japanese strongholds in Papua New Guinea.

"Japanese bases in New Guinea are being subjected to the biggest aerial offensive of the Pacific war, with gun positions, ammunition, gas and food dumps being ripped to pieces by the 5th Air Force," a correspondent wrote on April 13, 1944, in a dispatch that appeared in the next day's New York Times.

The article reported that 568 tons of bombs had been dropped in three days on Hansa Bay as "Gen. Douglas MacArthur's air arm obviously is intent on destroying the nerve centers of enemy resistance and paralyzing Japanese supply and communications lines."

Allied bombers flew through the "extremely bad weather" of the rainy season and left "destruction and death" up and down the New Guinea coast, the article said, but concluded: "Nevertheless our losses have been almost insignificant."

An article in The Baltimore Sun on March 22, 1945, noted that Moore's mother received an Air Medal with an Oak Leaf Cluster on behalf of her son, who was declared missing in action.

Moore's family decided it would be appropriate to bury him on Veterans Day. The military is planning a group service for the entire crew at Arlington National Cemetery, although a date has not been finalized, Morgan said.

For Charles Moore, whose father, also named Charles, was the eldest brother of the airman, the return of the remains brings back childhood memories that were fast fading.

He remembers his uncle driving a Hudson Terraplane car, although he can't remember the color. He also recalls going with his dad and uncle to watch them trapshooting.

And he remembers that night he was awoken to say goodbye.

"I was glad that happened," he said.

For Ed Warrington, there are also fond if faint memories, and a cache of letters that he still has from Uncle Hugh.

"The big thing I noticed," he said, "was he always closed by saying something like, 'I might not see you again.' "

http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/bs-md-wwii-remains-return-20141110-story.html#page=1